By Christopher Radcool Reynolds

Design is like a time capsule. It captures the aspirations of the moment during which it was made. I’m obsessed with historic design because it tells a visual story of our human experience.

If you know what to look for, you can see the story of San Francisco in its homes. In the earliest styles, you can see the growth of the city from a scrubby frontier settlement to a cosmopolitan city. Every era had its own look. Turn-of-the-century aesthetics show SF’s struggle with the advancements and losses of industrialization. During the last century, change happened crazy-fast. And modernist design reflects technological and social upheavals that transformed the city’s cultural and physical landscape.

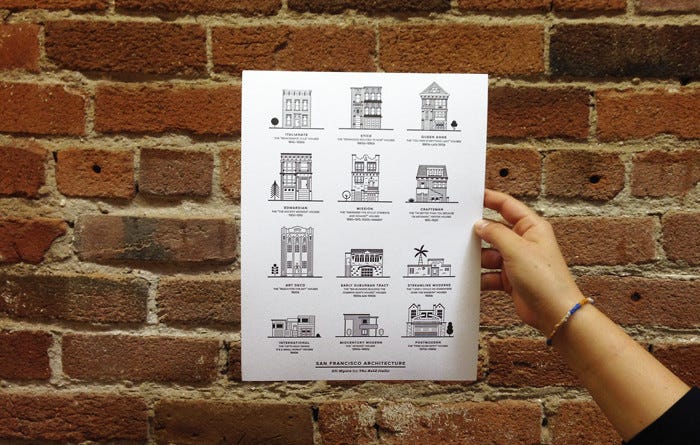

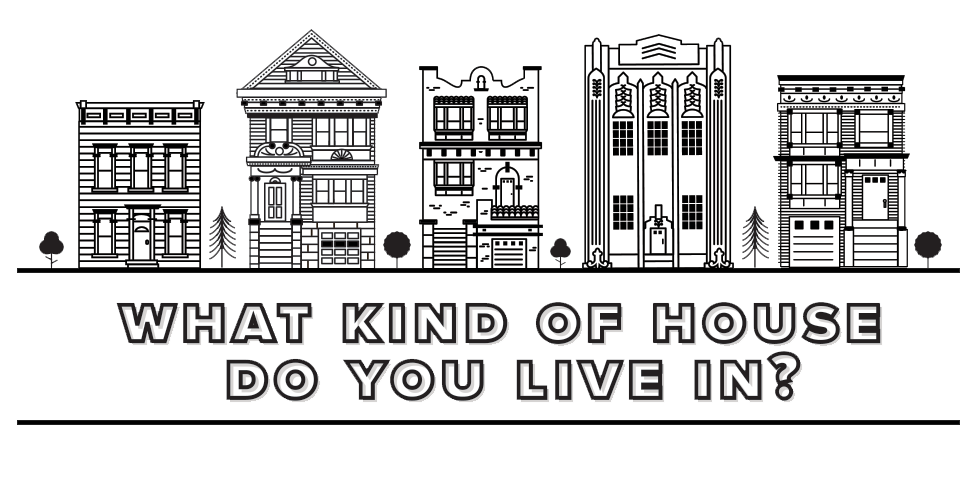

Here are the architectural styles of San Francisco homes. What type of house do you live in?

When the speculators of the gold rush arrived in 1849, the look of the day was Italianate, a movement that tried to re-create the look of the farmhouses and villas of the Italian countryside. The main decorations of these homes are the brackets at the roofline and the hoods over the window and doors.

SF’s earliest Italianates were just flat-fronted boxes, like the buildings you’d see in old Western towns, which the city really was at the time. As San Francisco and framing techniques became more sophisticated, multistory octagonal bays become an important element of this style. Italianates were once ubiquitous, but most burned down in 1906.

Examples of Italianate homes remain west of Divisadero and south of 20th Street in the Mission.

San Francisco was once surrounded by ancient old-growth forests. As the industrial revolution powered up, the city was ready for a style that used its natural resources. Redwood forests were reduced to two-by-fours. New framing practices made use of standardized lumber. Homes began to feature more complicated façades and roof lines. Once built, every imaginable surface was covered in bits of machined trim to create geometric patterns.

“Stick,” the name given to this style, embodies a tragic irony. Basically, the homes are built of and decorated with sticks — starting from the ancient redwood forests and ending in a neat forest of patterned homes.

Stick homes are common in neighborhoods that were untouched by the 1906 fire, such as the Western Addition, Noe and Eureka Valleys, the Mission and Potrero Hill.

In one hot second, San Francisco went from being a faraway outpost to a world-class industrial city. Its denizens wanted to show off all their new money with opulent houses. The designs were a free-for-all, precious and pretty. Queen Anne homes are fanciful and over the top. They feature countless combinations of bay windows, turrets and decorated roof lines. The trimming of these homes tends to be feminine and flashy. Like the Painted Ladies on Alamo Square, they are dripping in swags of flowers and shining with gold.

Extravagant examples of Queen Anne homes can be found in Ashbury Heights, Alamo Square, Cow Hollow and Pacific Heights.

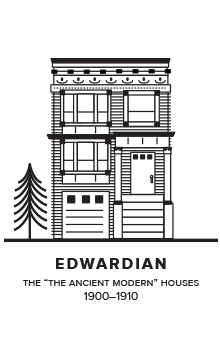

During the turn of the century, most of the Western world wanted to see itself as a direct extension of ancient Rome. San Franciscans, however, saw themselves as something new: modern.

San Franciscans had to work out the tension of being ambassadors of Western culture while living in a modern world. Enter the Edwardian home, where wives of industrialists could entertain in togas. Though less opulent than earlier Queen Annes, the more masculinely trimmed Edwardian houses borrow details from ancient temple architecture. Edwardians had fewer interior walls and featured larger “great rooms.”

Edwardian homes are highly concentrated in areas that were rebuilt after the fire, such as in SOMA, downtown and Mission neighborhoods.

Industrialization made San Franciscans face the harsh reality of modern city life and romanticize the simple rural lives of the city’s founders, the missionaries. The Mission style was an attempt to turn back time. It revived the look of Spanish missions, which had little decoration on adobe and stucco façades.

Key elements of Mission style were reinterpreted beginning in the late teens as “Spanish Colonial,” which is now the most influential style in California. It was used by tract developers to romanticize the western frontier. This nostalgia became an essential marketing gimmick to sell homes to midwesterners who wanted a piece of glamorous, sunny California.

Mission homes are found in Glen Park, the Sunset, the Richmond, outer Mission and Noe Valley.

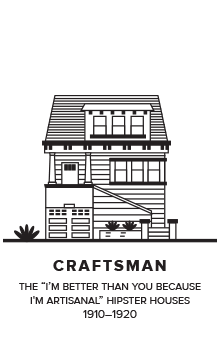

By the early 1900s, corporations and machines were producing everything. People feared that traditional crafts were going to be lost to assembly lines. The Craftsman home is not machined; it’s handmade by skilled craftsmen. The movement revived the trades by inflating them to art status. The Craftsman-style home has no added decoration. Instead, it champions the creation of a house into an art in its own right.

The irony of this style is that the movement elevates the status of handmade houses as being better than mass-produced houses. But like today’s artisanal and small-batch hipster culture, only the rich could afford it.

Craftsman homes were built away from the city’s center. You’ll find them in Glen Park, the Sunset, the Richmond, outer Mission and Noe Valley.

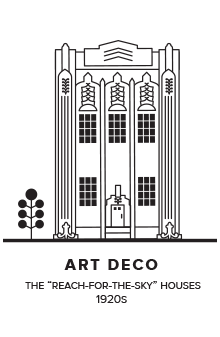

With a grip of steel and unchecked enthusiasm for industry, the buildings of the 1920s scraped the sky. Art Deco houses are heavily decorated in geometric patterns that play up verticality and give the illusion of a building vanishing into the sky. They feature modern or machine-age materials such as chrome, glass and steel. These buildings are all about optimism and technology.

As an embodiment of capitalism, this style was mainly used for commercial buildings, but a few Art Deco houses can be found in Pacific Heights, the Sunset, the Marina and Sea Cliff.

As families came to California to escape the Dust Bowl, developers had a big idea. They discovered they could make a ton of money by buying up the tracts of land outside the city center and building a multitude of nearly identical houses. For maximum profit, common floor plans were repeated over and over like an assembly line. The 1930s was the dawn of the subdivision trend that transformed the entire American landscape.

Developers relied heavily on hype — the San Francisco Chronicle wrote glowing articles about the new homes (while selling ad space to the developers themselves). And ever-changing stylized façades or new models helped keep the excitement (and profits) up.

These homes are ubiquitous in the Marina, the Sunset, the Richmond, Excelsior, Visitation Valley, Hunters Point, Bernal Heights, Noe Valley, Potrero Hill and Glen Park.

The desperation of the Great Depression left the common man dreaming of traveling to exotic places. Movies like The Wizard of Oz captured the nation’s longing to leave a drab existence by escaping to more colorful locales. Style in the 1930s was all about high-speed luxury travel. Aerodynamic detailing for trains and the horizontal decks and rails of luxury ships inspired the Streamline Moderne home. The low, long silhouettes are reinforced at every opportunity with horizontal details, and rounded corners evoke the bow and porthole of chic yachts.

Streamline Moderne houses can be found in areas that were the last to be developed, such as in the Sunset, Excelsior, outer Mission and Noe Valley.

The Depression made capitalism look really ugly. Socialism started looking pretty sweet. The world was ready for an aesthetic movement that embodied the new cooperative idea. International style was introduced as a style for the whole world. The 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island showcased this minimal architectural style, which drew inspiration from technology instead of history. The idea was to leave behind individual cultural identities and exist as one world. The International home drops any decoration that isn’t useful. No one had ever seen such simple square shapes. Today, many say they look like boring boxes, but at the time the clean lines were revolutionary.

International homes can be found in Noe Valley, Sea Cliff, Twin Peaks, upper Market, Laurel Village and Golden Gate Heights.

In the ’50s nearly everyone believed that very soon we’d all be living like the Jetsons. New materials made modern homes out-of-this-world. With few walls and tons of glass, it was hard to tell where indoor and outdoor started and stopped. You could drive your rocket-ship-styled Desoto right into your home and enter through the “carport,” a play on “spaceport.” By 1950 there was virtually no land left in San Francisco on which to build. That is, except for the most windswept peaks, which had previously been considered too hostile to live on. But new technologies made houses weather-tight, and areas were finally open to developers. After all, with views like those, who needed to go outside?

Midcentury modern houses can be found in Diamond Heights, Twin Peaks and Golden Gate Heights.

At first, minimalism seemed subversive, but to the children of the baby boom, it was bland, monotonous and predictable. Modern homes were seen as plain boxes, and it was time to think outside the box.

San Francisco was the epicenter of radical change. Civil rights, women’s liberation and the sexual revolution were mixing things up. Free love, drugs and rock ’n’ roll permeated youth culture. This anything-goes spirit let styles blend together. Like an architectural electric Kool-Aid, this style tends to appear weird, impossible, surprising or awkward.

Postmodern homes were built anywhere single lots remained undeveloped, like in the Sunset, Golden Gate Heights, Diamond Heights, Bernal Heights or where outdated industrial buildings were replaced — Potrero Hill, the Mission, SOMA and Mission Bay.

Illustrations by Eli Myers.