Last April, as the world was coming to grips with the magnitude of the coronavirus, Amy Brown passed through the courtyard of her San Jose apartment building. Up in a tree, isolated from other people and the ground, six-year-old Erik sat humming to himself. He seemed content up there, but also somewhat lonely and different from the energetic kid she knew him to be.

That’s when an idea struck that would change how she, Erik, and their community would live through the pandemic.

An artistic hummingbird, Brown has always been involved in different creative pursuits. She has a degree in English with an emphasis on creative writing, writes poetry, owns a plush toy company, and is a crafts instructor for children and adults. Before Covid-19 hit, she maintained exhibits at the Children’s Discovery Museum of San Jose. When the museum shut down, she, like many people around the world, was left dealing with the terrifying prospect of an uncertain future.

“Everything got sliced apart,” Brown recalls. “Nothing like this had ever happened to me. It felt awful from the start,” she says.

Stuck at home, she realized Erik — and the other children in her building — were probably also dealing with this uncertainty. As schools closed and California issued a shelter-in-place mandate, their daily lives transformed into something unrecognizable.

A couple of days after seeing Erik up in the tree, Brown left him a note with a simple question: “Do you want to be my science partner in an experiment?”

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

She received a response from an excited Erik almost immediately. They started planning a “taxonomy” project inspired by Brian D. Collier’s Very Small Objects. The idea was to collect tiny objects, less than a single inch, and use information like where they had been found, whether they had been alive, and their apparent function to give them pseudoscientific names.

Erik got to work straight away. “I just started getting all of these notes under my door and little tiny, tiny pieces of stuff in miniature plastic bags,” Brown says. Seeing his enthusiasm inspired her to open the project to the community.

While staying socially distant, she and Erik planned a mini-exhibition to be displayed in the hallway next to her apartment. They hung some of the objects they had found, leaving out printed naming guides for visitors interested in finding and naming their own small, everyday objects. They also made a now-defunct Facebook page and, eventually, an Instagram page so that they could get the word out.

The Ryland Museum was born. Equipped with a website and social presence, it was no longer just a project for Brown and Erik, but for everyone who was part of their community.

“Our children’s lives had changed drastically — all the fun activities of childhood were canceled overnight,” recalls Nicole Leko, one of Brown’s neighbors. “We were all so excited when we found out that Amy had created a little community museum in our building.”

Her 11-year-old son, Julian, agreed: “The museum has been so much fun,” he says. “I loved running down the hall with my sister and my friend to visit it.”

Even with the positive community reaction, Brown hadn’t necessarily thought of extending the project beyond the first exhibit. But by then, Julian had become fascinated with the idea of an RV road trip, and since his parents didn’t concede to his wishes, he decided to write a note to Brown and her husband asking them to buy an RV that he could borrow.

With summer approaching and the pandemic extending, Brown decided that she would take Julian on an RV adventure, not on real wheels, but through a second Ryland Museum exhibit.

Brown promoted the Come On! Come On! Travel After Corona exhibit on her building’s community newsletter and on Facebook. Placed along a winding cardboard paper road were about a dozen drawings of beaches, cabins in the woods, and cities full of skyscrapers, submitted by children (and adults), mostly from her building. The children got to “travel” and dream of life after the pandemic, but they also got to feel the pride of having their work displayed.

“It felt really good to see my art in the exhibits,” says Julian.

Erik’s mom, Karin Ikavalko, has observed the same feeling of pride in the other participating children, explaining that “it makes them feel part of something special.”

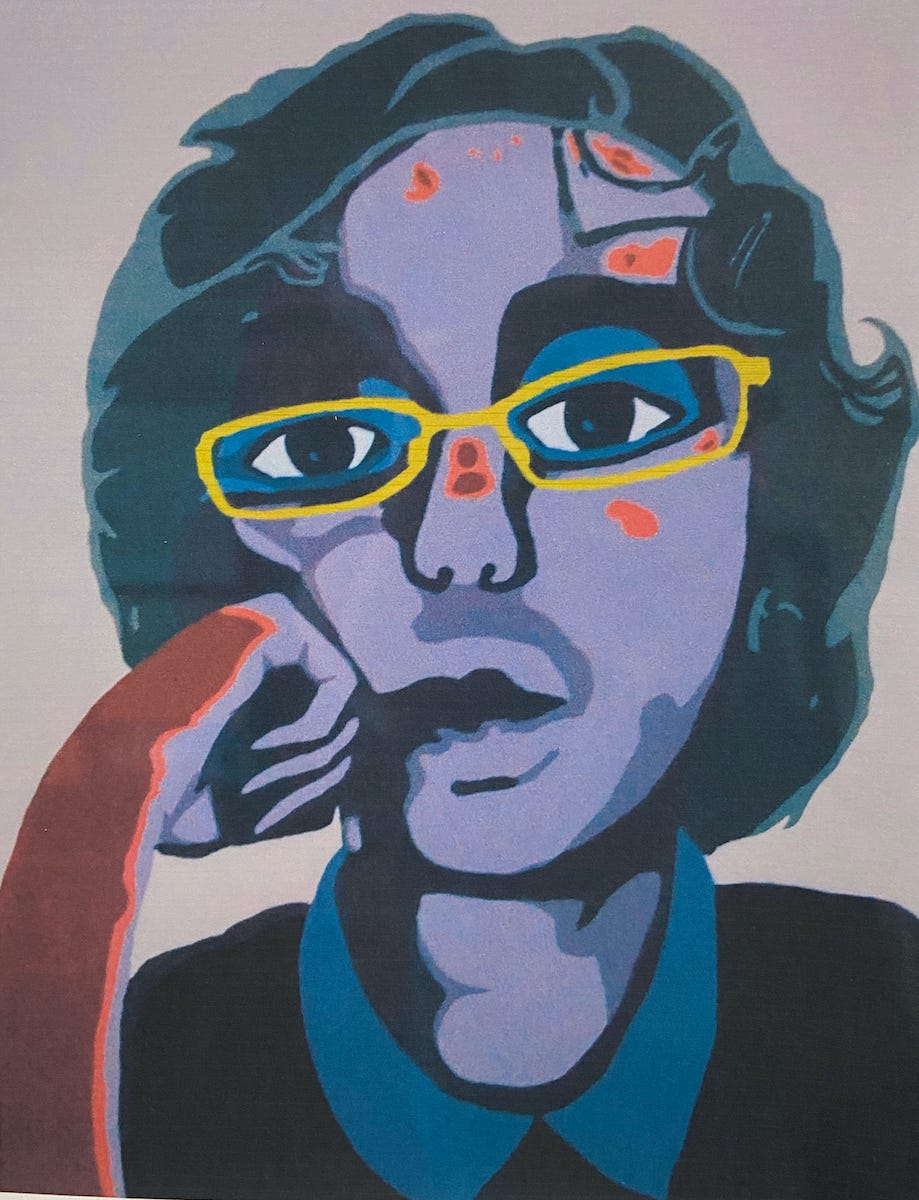

With this purpose, Brown based the themes for her next exhibitions, Portraits and Animals, on the suggestions and interests of other kids she knew in her building. For tiny, improvised art exhibitions, their success was impressive: both received about 30 submissions, about half from the building, and half from around the country.

As the museum grew, so did the sense of community.

“It has been a wonderful way of staying connected and keeping our spirits up, especially for the children, who feel so happy to be part of a community project and to still be connected with each other,” Leko says.

Ikavalko agrees, saying the museum “brightens the hallway in our building.”

“Seeing the collection of art from kids and grown-ups, submitted from people not just from our building but from many different communities, fosters a sense of connection,” she adds.

For Portraits, Brown took things to the next level by making a printable book of all the pieces that were displayed in the exhibition.

“I wanted the kids not only to have the recognition of having their work in this gallery but then to also be able to hold a book [with] their artwork in it,” she explains. Brown also made two book versions for Animals, and, at Julian’s insistence, is now retroactively working on one for the Travel exhibit. Ikavalko bought the books as a birthday gift for her older son, Kai, stating that “this will be a time that we all remember in the future, and the books will be something positive to hold on to.”

The current Ryland Museum exhibition will be on display until mid-November and follows a theme that feels particularly relevant: Home. People all over the world were and continue to be confined to their homes, others have lost their homes to wildfires whose hunger is made more voracious by the changing climate, and homeless people across the West Coast have been forced to face both tragedies without shelter or protection. As a nation, we’re grappling with the threat of violence faced by Black people both within and outside their homes.

For the artists, it was also a chance to explore what “home” means. Hana Rusi, a 17-year-old artist from Pennsylvania, submitted a picture of an oil painting of her great-uncle and his goat, which reminded her of her parent’s homeland, Albania. “I am happy that my art was included in the collection,” she says, and hopes to participate in similar projects in the future.

Rusi’s sentiments speak to Brown’s ultimate goal: to make art more accessible to children and encourage them to take on creative pursuits, a goal that extends beyond 2020 and the pandemic. She’s applied for a grant to give free copies of exhibition books to every participating artist under 18, and she’s also looking to take the museum outside of her building: “I would like to get in touch with [the] San Jose Parks and Recreation Department and see if there’s a way to use a wall in a park and have an outdoor exhibition.”

If the project continues to grow, she hopes it will inspire “kids from everywhere, from all kinds of backgrounds, to know that their art is important and that what they collect is important.” So far, she seems to be succeeding.