By Jeremy Lybarger

There are approximately 530 single resident occupancy (SRO) hotels in San Francisco. They are home to more than 18,000 people, the majority of whom live in low-income neighborhoods such as the Tenderloin and Chinatown. A 2009 report from the Human Services Agency listed average monthly rent at $500 to $600, but it’s not uncommon for tenants to pay as much as $1,000 for an 8x10 room with no bathroom or kitchen. As San Francisco’s cost of living continues to explode, many housing activists worry about what will become of the vulnerable SRO population. Between 1970 and 2000, the city demolished or converted to condos 15,000 SRO units. Life has always been precarious for these residents and far from idyllic in even the best-managed buildings. Here are the stories of six people trying to survive in a city that’s increasingly out of reach.

CYNTHIA

MISSION HOTEL, MISSION

The Mission Hotel, with 248 units, is the largest SRO in the city. Outside it looks like stale cake. Inside it’s all institutional seriousness: lime-and-beige tile floors, walls of lime-and-beige concrete, cagey fluorescents. On the day James (the photographer) and I visit, two cops have staked out a wedge of sun from which to watch passersby with casual contempt.

Cynthia has lived here for a year and half. She came to San Francisco from L.A. For reasons unclear to me, her car caught on fire en route and incinerated most of her belongings. Her mother invited her to Missouri to regroup and get her life back together, a period Cynthia dismisses as one of snowy boredom. A self-declared Deadhead — a faux street sign on her wall reads DEAD HEAD WAY — she always yearned for San Francisco, the promised land about which Jerry Garcia sang: “Some folks would be happy just to have one dream come true / But everything you gather is just more that you can lose.”

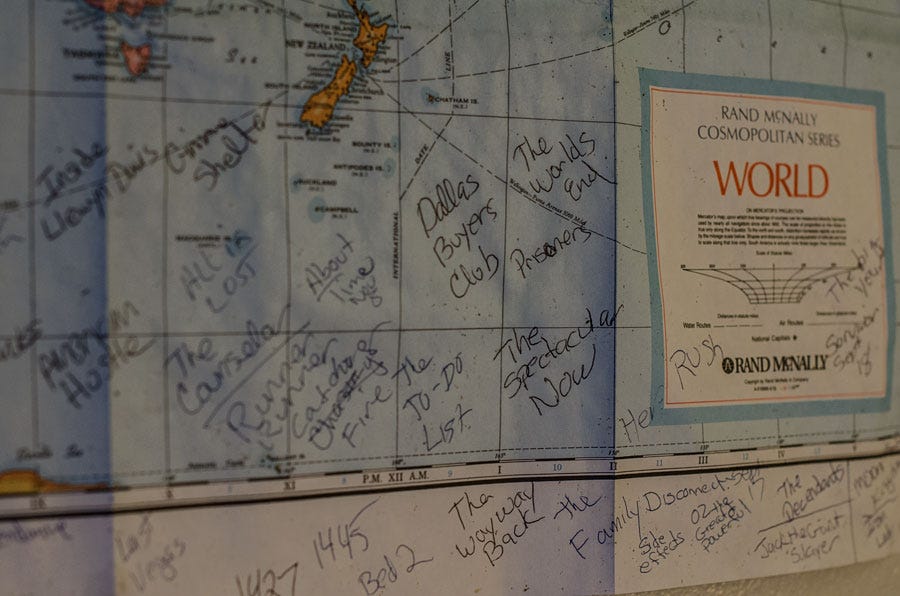

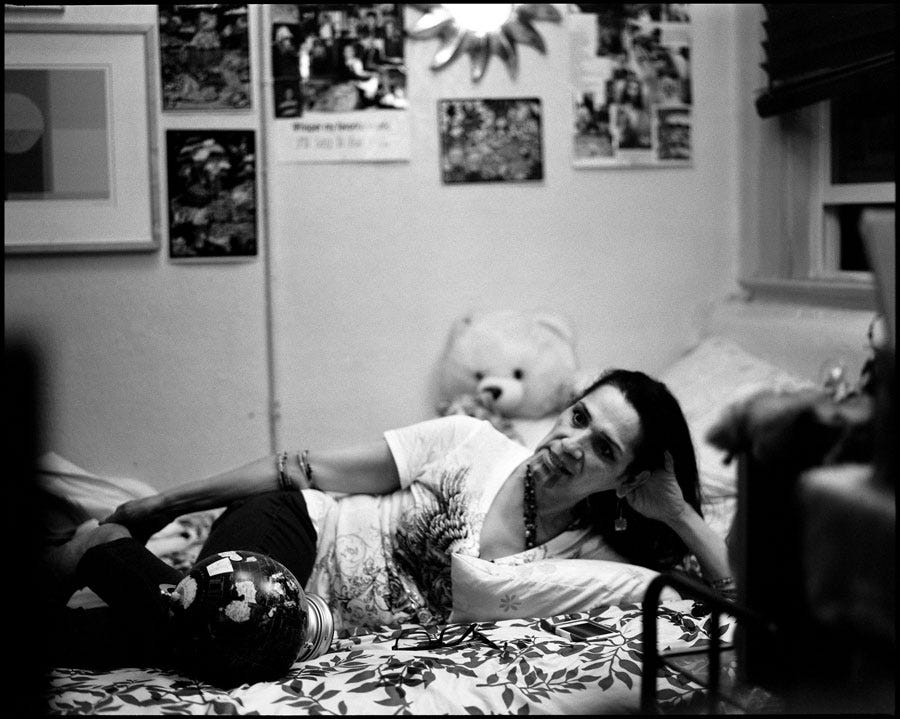

Her room here is small and comfortably lived in. On warm days she props open the door and hangs a beaded curtain that lets fresh air through. There’s no bathroom or kitchen. A microwave and a $20 hotplate from Goodwill take care of most meals. A blanket printed with Van Gogh’s Starry Night, salvaged from Golden Gate Park, is tacked to the ceiling. On the wall beside the bed is a map of the world on which she jots the names of movies to rent from the library. The hotel shows movies on a flat-screen TV in the lobby, but Cynthia rarely ventures down since what’s playing is usually horror. Her tastes run more toward Nora Roberts romances, a paperback copy of which lies on her bed. This is what’s so charming about Cynthia: She’s gentle and unassuming, with a nervousness that she disguises by fussing with her dog, Maggie. “She barks when she hears people on the fire escape,” Cynthia says, gesturing to the window. “I put a screen up because I worried about people poking their heads in at night.”

Life at the Mission Hotel is generally quiet. There was a cockroach problem for a while, which persists in neighboring rooms, but Cynthia says her place is bug-free. At any rate, it’s nicer than her last address, the Civic Center Hotel, where roaches frothed out of the ceiling. Asked how long she plans to live here, Cynthia says, “I’d like to get a studio apartment someday, but I don’t know if that will happen.” She fantasizes about a program where SRO tenants could graduate to larger, rehabbed apartments with private bathrooms, while homeless people would be transitioned into SROs. It’s a generous proposal but unlikely to happen in a city where average rent for a one-bedroom apartment is $2,800 per month.

In the meantime, Cynthia attends regular tenants’ rights meetings and advocates for more equitable low-income housing. A sign over her bed says HOME SWEET HOME without irony. And it’s probably true that home is as much a state of mind as a place to be. As we head back to the lobby, a man on the stairs stumbles and laughs to himself in the half-light. “Let’s try that again,” he says, pulling himself up.

CALVIN

APOLLO HOTEL, MISSION

Calvin should be dead. When he was 17 a stroke left him paralyzed for three months. He couldn’t talk for several days and communicated by blinking. He still drools occasionally, but at 50 he seems healthy enough — a small, talkative man in pajamas and an oversized T-shirt. “The next one will probably kill me,” he says, lighting a cigarette.

Calvin lives in the Apollo Hotel on Valencia Street. It’s a clean, sunny place with hardwood floors and potted plants commandeering every alcove. On the way to his room we pass a small nook where an old woman is watching a courtroom show on TV. She glances up briefly and smiles out of a bony face.

“I’ve lived here nine years and I ain’t going nowhere,” Calvin tells me. His room is a little square crowded with shapes that gradually resolve into identifiable things: a wooden backscratcher over the bed, a printout from his mother’s funeral, a potbellied jar about one-fourth full of change, a prescription pill bottle holding a handful of M&M’s. A tree outside the open window rustles like money. “If I had a choice between the street and here, I’d pick here. If I had a choice between here and a mansion, I’d pick the mansion,” Calvin says.

He neglects to mention an even worse option: prison, where he served 13 months for drug possession. San Francisco was a different city then, he tells me. All along Mission and Valencia, edgy young men leaned against buildings or parked cars, smoking crack and flashing gang signs. There was a murder almost every night in the SROs. People were stabbed. The paddy wagon was more or less permanently double-parked in the neighborhood.

“The city gives people freedom that doesn’t exist in other cities,” Calvin says. “You can go outside dressed like a pumpkin and nobody says shit.” For Calvin, that freedom led to a wormhole of addictions: cocaine, crack, meth, heroin. In prison, a motivational speaker awoke in him the possibility of redemption. “He told me: ‘If you keep doing what you’re doing, you’re going to keep getting what you’ve got.’ I decided from that day on to stop.”

Calvin has been sober 11 years. He still drinks and smokes a little weed, but who doesn’t in San Francisco? He can’t imagine ever leaving the city. He was born in Bayview, grew up in the Mission, and plans to die on the same hallowed ground. He can barely imagine ever leaving the Apollo. Life is peaceful here, save for the man who runs naked to and from the communal shower. “It’s true I can’t rip and run like I used to,” Calvin says, but in his mouth the words sound almost like amen.

BRENT

DONNELLY HOTEL, MID-MARKET

To enter Brent’s room is to enter an alternate reality. Blankets over the window blot out any trace of daylight. The ceiling is a bootlegged midnight of cotton clouds and plastic stars suspended from wires. Toby, an obese Jack Russell terrier, growls and chomps at our ankles. Everything has the humid incense of dog breath.

“He’s the love of my life,” Brent says about the animal. And like any great romance, theirs is fraught with petty vindictiveness. One moment Brent cradles Toby and whispers endearments into the dog’s ear — You handsome boy — and in the next he calls the dog a fat ass and hurls him to the floor.

They’ve lived in the Donnelly Hotel eight years. It’s the kind of building you would imagine an SRO to be if you’ve never been in one: a dim warren of rooms connected by the musk of cigarettes and old carpet. The hallways are narrow and yellow-lit. The elevator is permanently out of order. Brent’s window faces Twitter and the vertical black sheen of the NEMA luxury condos.

Since the Donnelly is an independent hotel not managed by a nonprofit or outreach agency, turnover is high and tenants’ mental stability variable. “It’s basically like a world’s fair in here,” Brent says. As a gay man, he’s endured a lot of harassment. “I’ve heard the word faggot so many fucking times.” Three years ago, friends of another tenant assaulted him in front of the building. Brent pressed charges but was unwilling to navigate what he describes as San Francisco’s labyrinthine court system. More recently, his upstairs neighbor attempted to force his way into Brent’s room and punch him “for absolutely no reason.”

Perhaps more disturbing is the behavior of his next-door neighbor. “That guy, I swear he sold his soul to the devil.” At one point the neighbor set up cameras to record the hallway and apparently still has several more in his window running surveillance on the street. At night he taps the baseboard in his room for hours, “trying to bore a hole to stick his little three-inch dick through,” Brent says.

Despite these incidents, Brent is content at the Donnelly. When he first came to the Bay Area from Seattle in 2001, he was homeless and lived out of his car. He worked sporadically as a drag queen in the Castro — Miss Sharon Needles before the Sharon Needles — and got a monthly allowance from his mother, but it wasn’t enough to keep him afloat. “I manage my damage very well, and I’ve never hit bottom,” he says now about that period.

He recently bought a flower printer and plans to run a business out of his room selling personalized roses. “This is a multimillion dollar industry,” he tells me. “Once production takes off it’s going to be crazy in here.” As Toby growls to himself somewhere in the near dark, Brent offers a last word of advice: “Don’t take anything for granted, because once you do shit will be taken right out from under you. And believe me: You can’t change death. It’s going to happen and you better fucking deal with it.”

RONNI

ARANDA RESIDENCE, TENDERLOIN

The Aranda Residence sits between a bodega that sells fried chicken and a liquor store that sells 40oz. holidays. A posted sign advises NO LOITERING OR ILLICIT ACTIVITIES WITHIN 20 FEET, which is precisely what’s happening on this block of Turk Street. Customers shamble out of Club 21 on the corner, their faces going one direction while their legs go another. Men stare with unnerving familiarity, but whatever they’re looking at isn’t you. It’s more like that occult talent by which cats are supposed to discern auras.

The Aranda has the drab serenity that institutional places often have. We’re signed in by a desk clerk about whom the phrase world-weary barely does justice, then dismissed to the third floor to meet Ronni. Her room is the biggest of the six we visited, with a private bathroom and a kitchen area that includes a full-size refrigerator. Everywhere you look there is vivid and haphazard evidence of life: ceramic Seven Dwarfs figurines, a stack of motorcycle magazines, a plastic skull with glow-in-the-dark eyes, a reproduction of Warner Sallman’s The Head of Christ. But everything also has its place, a tidiness at odds with Ronni herself.

I can’t say how a psychiatrist might diagnose her, but schizophrenic seems reasonable. She has the wall-eyed intensity of a cultist peddling a leader’s teachings or a telepath scanning brainwaves. She speaks with precision and conviction about impossible scenarios. “I am Christ,” is one of many bombshells that emerge during our interview.

Ronni was born on the Yurok Indian reservation in Humboldt County. She knew early on that she was different. She was born and raised a boy, but her testicles never dropped and she felt more comfortable as a girl. Her family didn’t accept her. She hints at several traumatic episodes, including a rash of disappearances somehow connected to her. “No matter how far away I get, they’re still here,” she says about her family.

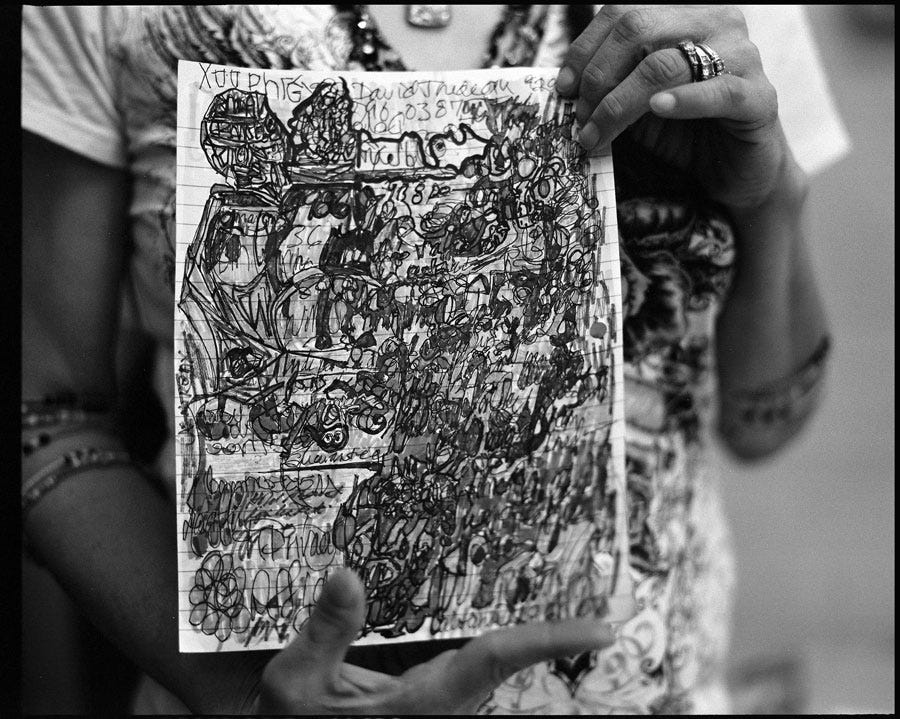

She came to San Francisco 11 years ago and has lived in the Aranda since 2007. She rarely ventures out. Most evenings she uses a little speed and writes in her notebooks until morning. What looks like hundreds of closely scribbled pages are filed neatly in color-coded folders.

She takes dictation from various sources: ghosts, phantoms, family members, and ancient gods who counsel her about Mu, the land of the dead. “Look here, can you see the faces?” she says, holding a tiny mirror — the kind used to cut cocaine — slantwise against a page of cramped calligraphy. I can’t see anything except the snarled beauty of her penmanship.

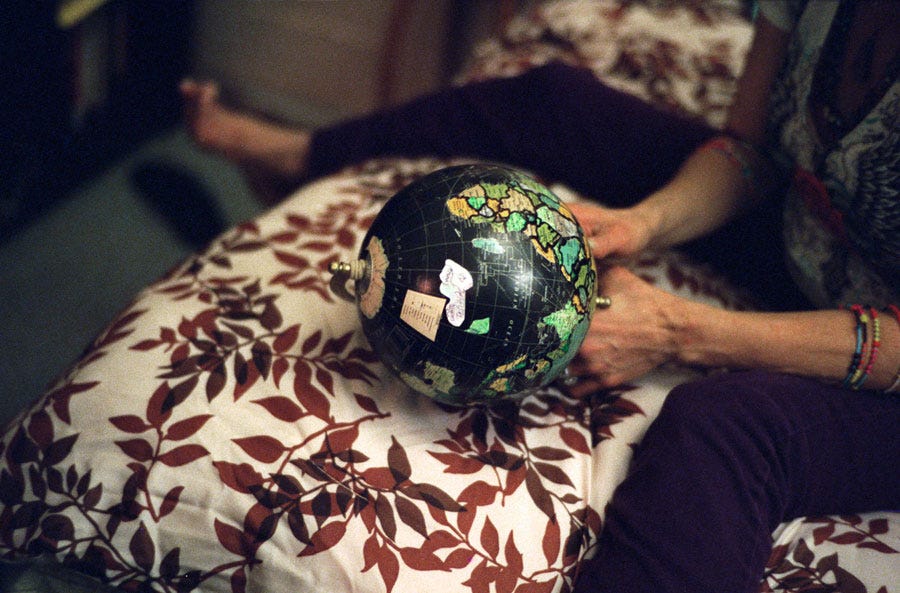

Ronni pulls a globe from her shelf and explains how she’s been instructed to divide the world. First, she turned the earth upside down on its axis. Next she used a knife to scrape off countries deemed offensive. Then she used a sharpie to bisect the United States along the length of the Mississippi, declaring everything east of the line Tornado Alley and therefore expendable. “I feel the burden of centuries,” she tells me with something like noble sadness in her eyes.

She also feels the impossibility of ever escaping her demons. A hit man recently teleported into her room with the intention of killing her. After several hours Ronni persuaded him to punch her in the face instead. The only place she really belongs — the motherland she’s working toward and might reach thousands of years from now — is the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. All of this complicated theology will make sense in the desert, she says. “For the longest time I felt retarded. Nothing would compute. All I could see were two answers and no question.”

Before we leave, she offers to conduct a purification ritual. She lights a gnarled twist of Angelica root and waves it over our heads and hands while intoning a prayer in her native language. Then, in English, she asks God to protect these two men who have been so kind to her. As she speaks, I stare at a metalwork sign on her wall that says AND THE TWO SHALL BECOME ONE.

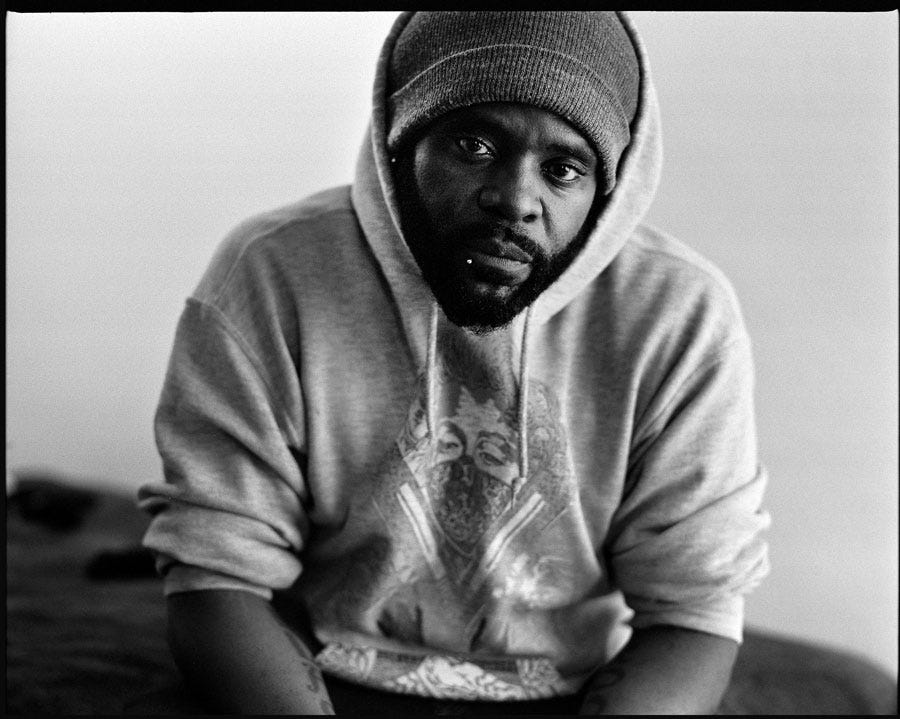

CLARENCE

CANON KIP COMMUNITY HOUSE, SOMA

Clarence was born in Ingleside, a working-class neighborhood bounded on the north by Ocean Avenue and on the east by I-280. His father was killed by a drunk driver. His mother was a workaholic. As an only child, he had a lot of time to think about what he wanted from life. He didn’t expect the solace of drugs, but as a teenager he discovered crack and subsequently subsidized his habit by dealing and gunrunning. He dropped out of high school. Eventually he was arrested for drug and firearm possession. It was a dark time made worse by his mother’s death and the mismanagement of her estate — Clarence alludes to a lien on the house and a malicious cousin.

With nowhere else to turn, he got a bed in the Sanctuary, a men’s shelter administered by Episcopal Community Services. He describes it as a ward of broken men who coughed and cursed all night. In the morning, half a dozen would file into the bathroom and shit on everything. After his first night, Clarence personally visited every outreach program and social service agency in the city, offering to work in exchange for a room, signing his name to inexhaustible wait lists, pleading with low-level bureaucrats whose hands were tied. It was nine months before a room opened in Canon Kip Community House.

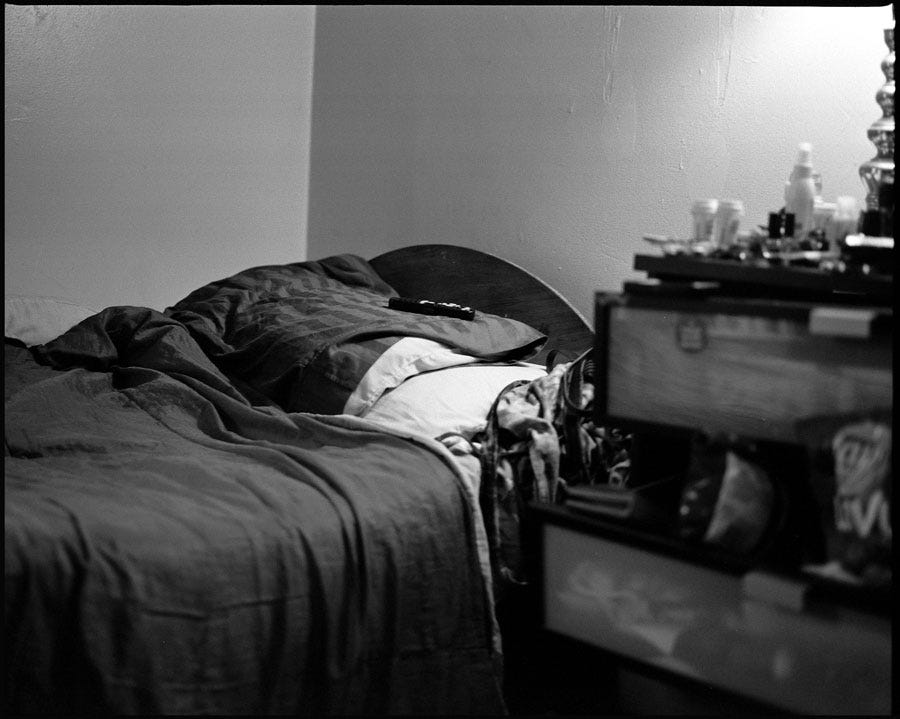

The building, like the Mission Hotel, has an institutional severity only partially relieved by a rooftop deck. “It might look like a condo but don’t let that fool you — it’s an SRO,” Clarence says. He has lived here for a month and a half and hasn’t done much by way of decorating. The walls are bare. The only furniture is a bed, a chest of drawers, and a stand on which sits a junk TV. He recently bought a rug that matches the floor, but it’s still rolled up and now serves as a place to hang his coat.

Outside on Natoma Street men await salvation amid halos of crack smoke. Their grizzled voices drift into Clarence’s window at night, reminding him of a fate that was almost his. “You can smell crack in the hallways sometimes,” he says. “Before I moved in, a friend warned me not to get caught up in the essence of the building.” When I tell him he seems to be succeeding, he smiles and says that it’s possible to feel grateful and depressed at the same time. “Don’t get me wrong, I’m happy to have this place, but I definitely want to get out.”

In July he’s going back to school to earn his diploma. He attends the same monthly tenants’ rights meetings as Cynthia and educates himself about housing policies. When I mention the prospect of going to another city, somewhere more affordable, he replies: “I was born here and lived all my life here. Why should I have to leave?”

JUN & FAMILY

CHINATOWN

Nothing indicates that this wood-framed, three-story building is a residential hotel. It sits halfway down a dead-end alley in Chinatown, tucked away from the bustle of Grant Avenue. Laundry flutters in every other window. Inside everything is raw wood, the color of matchsticks.

The walls are dingy and the ceilings singed-looking. When we enter Jun Tan’s apartment, I think at first that we’re in a little girl’s bedroom. There’s a small bed canopied by pink curtains and shelves glittery with porcelain. I count at least six calendars on the wall, the oldest dating 2011. But this can’t be a child’s room because here, at the foot of the bed, is a refrigerator and a wok, a rice cooker, sheaves of bok choy. There’s a sink beneath a speckled mirror. And there, quiet and stolid, not meeting her own reflection, is Jun Tan’s wife preparing dinner.

Jun, his wife, their eight-year-old son, one-year-old-daughter, and Jun’s in-laws share these two rooms. Jun and his family live in the back — the room with the bunk bed — while the in-laws live in the front with the canopied bed and kitchen. Privacy is nonexistent. Jun works nights as a janitor, so at least his wife has the bottom bunk to herself and can sleep easy knowing her parents are on the other side of the door.

The Tans immigrated to San Francisco from Canton in 2011. They moved into this hotel a year later. Life in the U.S. is better than in China, they say, but life in the hotel isn’t easy. Each of the two rooms in the apartment costs $900 per month. There is one communal toilet per floor (shared by 15 families) and one communal kitchen. In the morning, it’s not uncommon to wait 20 minutes for the bathroom. Sometimes the family uses a bucket in their room instead. The kitchen situation isn’t much better. Competition for the stove is around-the-clock and ruthless. Jun tells me that territorial chefs have been known to throw boiling water on would-be interlopers.

The building manager has banned microwaves, hotplates, and toasters, which is perhaps just as well given the hotel’s rolling blackouts. The room came equipped with a mini-fridge, but since it couldn’t accommodate enough to feed a family of six, the Tans discreetly installed a full-size model. Their son scouts around inside of it for a probiotic milk drink that is cold and sour. He takes one for himself, and a few minutes later returns for a popsicle. A while later he helps himself to seaweed and cookies, obviously pleased that his parents are too preoccupied to chaperone his appetite.

Jun is 44 but looks a decade younger. He’s thin and sinewy, with the tranquil fatigue that only fathers of very young children have. For the hour or so that we’re there, he never stops cradling his infant daughter, cooing to her, bouncing her on his knee, blowing her wisps of dark hair. There is a palpable feeling of tenderness and warmth. A breeze wafts through the window, stirring the clothespinned shirts and carrying the smell of onions and the sound of voices talking momentously in Chinese.

When I ask Jun what he’d like from life, he answers without hesitation: “My own house where I could cook and shower according to my own schedule. Those things are difficult here.” And also, perhaps, somewhere quiet, away from the bawl of sirens, which, he tells me, his son can imitate perfectly.

Thank you to the tenants who welcomed us into their homes and shared their stories, and to the following organizations for connecting us with them: Chinatown Community Development Center, Community Housing Partnership, Mission SRO Collaborative, and SPUR. Please consider a donation to support their commitment to empowering tenants through outreach and advocacy.

Photos by James Hosking

More photos here.