By Sam Harnett; Designed by Elizabeth Brown; Photography by Gundi Vigfusson

Each theater — abandoned, restored, or converted — has a unique history. Treasures, like the Fox, have been summarily demolished. Restoration projects, like the Alexandria in the Richmond, have been sidelined for years by city bureaucracy. Development plans for buildings like the Pagoda Theater, a decrepit shell of a building on the corner of Washington Square, have been repeatedly stalled by preservationist groups.

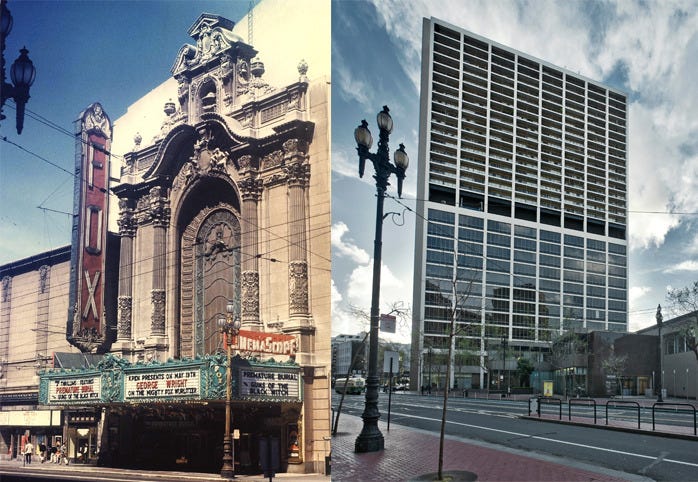

In the 1940s, at the height of the theater age, San Francisco had over a hundred movie houses. As people began acquiring televisions in the ’50s, theaters became unprofitable and began to close. The Cinema Treasures website lists 20 of the city’s theaters as demolished, 65 as closed, and only one, the Pagoda in North Beach, as currently under renovation. The last theater to run conventional movies on Market Street, the St. Francis Theatre, closed in 2000. On Mission Street, the Tower was the final theater to shut its doors in 1998. Jack Tillmany, the city’s preeminent theater historian, estimates that there are only about a dozen old cinema houses left.

The history, present state, and future of these theaters is something that both photographer Gudmundur Vigfusson and I find fascinating, so we decided to collaborate and see if we could explore them in person. Together, we set off in his bright-colored Volkswagen Bug, and as we drive, I rehearse pitches to convince developers and real estate agents to let us shine some light onto their long-forgotten interiors. Gundi and I agree to start our ghost walk on Market Street, once the city’s central nightlife artery, now the city’s premier theater graveyard.

Midday approaches and newspapers blow down the street like tumbleweeds in a Dust Bowl town. It’s hard to imagine mid-Market as anything other than a wasteland of boarded-up businesses and the stragglers of failed social programs. In Jack’s book, Theatres of San Francisco, there’s a photo of Market Street ablaze with the marquees of 30 theaters and bustling with the evening dresses and fedoras of 25,000 moviegoers.

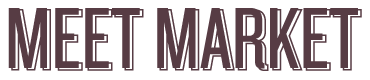

Market Street theaters, Jack explains, had first rights to American films. Neighborhood theaters could screen a movie only one month after it had finished running on Market Street. Cinema owners took advantage of that privilege and crammed 25,000 seats into a six-block radius. The strip started with the smallest theater, the 400-seat Silver Palace on 3rd Street and culminated on 9th with the 4,651-seat Fox Theatre, an enormous spectacle of baroque architecture. At the time it was hailed as “the last word” in lavish theater.

In 1963, the Fox Theatre was smashed into the earth by a team of wrecking balls. It was demolished with the overwhelming support of a generation that was looking forward to modernization, not backward to history. The city was given a chance to vote on the destruction and it did so by a two-thirds margin.

Gundi and I wander into the concrete tower of office buildings, retail spaces, and apartments looking for some scrap of the past. At the desk, an officious receptionist cocks his head when I ask if there is anything to commemorate the old Fox Theatre — some kind of placard or engraving. His heels click against the floor as he leads us into a lowly lit side exit with two black-and-white photos of the baroque theater on the wall. Not much left of it, he says with a dry chuckle.

The brutal retirement of the “Fabulous Fox” became an instant rallying call to forlorn theater preservationists. The movement, headed by the San Francisco Neighborhood Theater Foundation (SFNTF) and Friends of 1800, has since prevented buildings like the New Mission and Harding Theaters from being demolished by developers. In 2007, SFNTF purchased and reopened the Vogue, one of the city’s rare 100-year-old movie houses. It has been a significant victory for preservationists, especially since word leaked in August that Landmark Theatres would be closing another centenarian, the single-screen Clay Theatre on Fillmore Street. The Clay has narrowly avoided closure so far, but longtime plans for the theater are still up in the air.

Gundi and I follow a thin man pushing a shopping cart down Market Street. We pass the Orpheum and Warfield, old theaters that have survived by reverting to live performance spaces. Every other theater has either been destroyed, converted into a strip club (Market Street Cinema) or boarded up by developers. The last two standing abandoned movie houses on Market are the Strand at 7th Street and the St. Francis Theatre near Mason Street — both glaring examples of development left in the wrong hands.

At our next location, the Sun Sing Theatre, I think I’ve found the spot where in 1947, Orson Welles watches a Chinese play while he waits for Rita Hayworth. It’s right between a glass cabinet filled with golden good luck kitties and a pile of electronics from the ’90s.

Appropriately, what was once the Sun Sing and the on-set location for the culminating scene of The Lady from Shanghai is now a market filled with vendors selling cheap Chinese goods. No one stops us or even seems curious when Gundi and I drift up a side staircase to the overhanging balcony crammed with boxes.

The Rialto Theater in the Outer Mission has been the Billiard Palacade for much longer than it was a theater, but the details inside have been preserved much better than most in the city. We sidle up to a bar that still looks like an old ticket counter as regulars lightly knock away balls under the soft pool lights. The elder El Salvadorian woman explains the history of the place as she wraps our beers in napkin koozies. In American Graffiti, parts of the building are visible on the fringes of a scene shot at what used to be the Mission Drive-in across the street. The drive-in was replaced by apartments in the mid ‘80s.

The empty marquees of five old theaters line six blocks of Mission Street between 19th Street and 23rd. Jack figures that the Tower, El Capitan, New Mission, Cine Latino, and Grand Theaters held about 7,500 seats. Tower Theater is up for sale, El Capitan has been turned into a parking lot, the New Mission sits in development limbo, the inside of Cine Latino has been gutted for redevelopment, and the Grand Theater has been turned into the Hajvery One Dollar Only store. We hope to get a peek inside one of these theaters, and we’re in luck when we’re able to track down a perky young real estate agent who agrees to let us into the Tower.

The break-in damage in the New Mission is just a small cut on the surface of years of neglect. A leaking roof let in damaging rainwater when City College was trying to turn the building into the new Mission campus in the early 2000s. Preservationists got the theater landmark designation and succeeded in preventing City College from dismantling it. They had high hopes when the developer of Medjool Restaurant/Lounge, Gus Murad, acquired the building in 2003. The realtor opens the The New Mission’s doors for us while he chatters outside on his BlackBerry. Gundi and I walk in alone.

The inside of the New Mission is cold and damp, like being inside a mausoleum. It seems like time this theater saw any lively activity was when a bunch of kids broke in a few years ago. The flood lamps cast shadows on the evidence of their revelry: incoherent peace-and-love graffiti and crushed cans of cheap beer. The New Mission may not be as preserved as the Tower, but the power of the space gives any living soul a hair-raising tingle.

Gus leads us in past the piles of furniture from the last tenant — Evermax Home Furnishing and Gifts. As we walk through the enormous sloped seating area, Gus shines his flashlight onto rusted metal beams and crumbling plaster. This is all new he says. When it was a furniture store, Gus says he would come in just to admire the architecture, not to buy anything. Now he owns the building and says when he comes in here it just makes him depressed.

Gus has been struggling with the city to launch a development project to renovate the theater. The plan would include creating affordable housing on the site of the Value Giant next door. Controversy erupted in 2005 over how high Gus could construct the housing units. The city claimed the 85 feet exception for the lot had been a typo in an area that should only be zoned for 65 feet. Those 20 feet have since kept the project in limbo.

As we leave the theater, Gus can’t keep the bitterness from his voice when he says he could better estimate when he is going to die than when he’ll finish the renovation.

It’s been several days since shooting this project, and I’m thoroughly spooked. I see dead theaters. Some are frozen in the agony of their final moments, faces covered with graffiti, frames draped with the architecture of a long-gone age. Some are sitting around like regular buildings — people going in and out to buy prescription drugs, exercise, eat a burger. I see them everywhere — blank marquees staring out over churches and Walgreen’s, dark projection room windows peeking out into 99-cent stores, art deco facades blending in with the other buildings on the street. The saddest part is that most people don’t know that these standing dead were once living, projecting theaters.

The best way to save old theaters is to go out to a movie. Patronize the centenarians — the Vogue, the Clay, and the Roxie. The Red Vic theater is currently accepting donations to combat its financial woes.

Vintage photos by Jack Tillmany